Yogyakarta

Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival

Yogyakarta

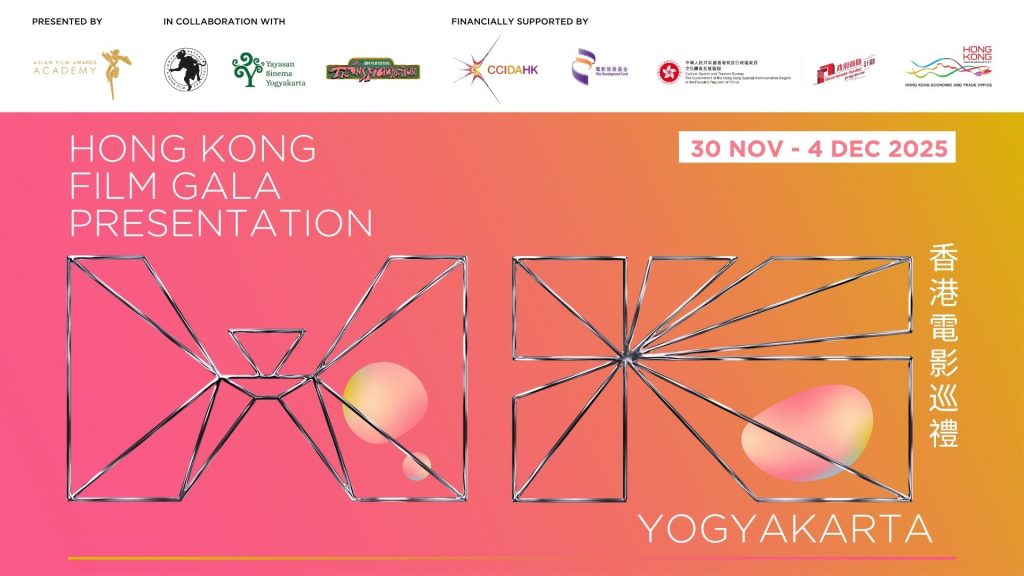

Date: 30 November – 4 December 2025

Location: Yogyakarta, Indonesia (Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival)

Guest: Ann Hui, Man Lim Chung, Robin Lee, Mandrew Kwan, Quist Tsang, Ivan Cheung

Screening: July Rhapsody, A Simple Life, Keep Rolling, The Remnant, Sons of the Neon Night, Four Trails, Another World, Someone Like Me, The Killer (Restored Ver.), The Apple of My Eyes, Tomatoes are Poisonous

Partner: Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival

“A ‘work’ doesn’t necessarily have to be a narrative feature film. As long as it expresses the creator’s ideas, one can already be considered as a director. With a smartphone, filming and editing have become incredibly easy. At the beginning, I was worried, because when everyone can be a director, the training we once received seemed no longer important. But later, I realized this is actually a good thing”, Director Ann Hui candidly shared her views on the contemporary film and media landscape during a masterclass organized by the Asian Film Awards Academy (AFAA).

The Hong Kong Film Gala Presentation – Yogyakarta, presented by the Asian Film Awards Academy (AFAA) and in collaboration with the Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival (JAFF), is funded by the Cultural and Creative Industries Development Agency (CCIDA) and the Film Development Fund, with support from the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office (HKETO) in Jakarta.

Ann Hui Masterclass was one of the highlight programs of the 20th Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival and the Hong Kong Film Gala Presentation – Yogyakarta. Hui shared her filmmaking journey with local audiences and young filmmakers in Yogyakarta, encouraging them to learn from classic films and recognize their lasting value in shaping future creations. She also emphasized that the true driving force behind artistic creation should come from a love for creation itself, rather than the pursuit of fame.

The masterclass officially began with the screening of two tribute videos revisiting Ann Hui receiving the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Film Festival and the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Asian Film Awards, prompting enthusiastic applause that carried from the screen into the venue. Dressed simply with a warm smile, while the moderator was introducing her, Hui quietly lifted her phone to take a photo of the audience, capturing the precious moment from the event.

With a career spanning over fifty years, Ann Hui’s works cover a wide range of genres, from social realism to entertainment types. When asked how she views the role of a “director”, Hui explained that the role changes depending on the production context. For example, during the making of July Rhapsody, she worked from a completed script written collaboratively with another screenwriter, serving primarily as a director executing the script. In other cases, when the story originates from her own ideas, she becomes more like the author of the film.

She shared, “In Hong Kong, directors usually don’t have a fixed production team, but what remains constant is that the director is the person responsible for bringing the story onto the screen.”

“I only wanted to understand cinema better. I never thought of becoming a director,” Hui recalled. She enrolled at the London Film School in the late 1960s, where the mode of learning was entirely new to her. “I’m not timid, but I’m more introverted and don’t talk much. Film school was very inspiring. My postgraduate education focused heavily on concepts, but it was only when we actually picked up cameras and started filming that I felt closer to the real life and gained a more grounded understanding of cinema”, she said that she was less skilled in technical aspects compared to her classmates, but since she could write scripts, she took the role of director. It was at London Film School that she came to a realization: “All art originates from life.”

Speaking of Ann Hui inevitably leads to the Hong Kong New Wave. Hui returned to Hong Kong in 1975 during a period of transformation in the local film industry, which was shifting from kung fu and martial arts films toward more socially grounded stories. Alongside fellow New Wave directors such as Tsui Hark, Yim Ho, Allen Fong, and Patrick Tam, Ann Hui first worked in television drama production. She recalled, “Film investors saw our works from television series and thus approached us to make films.”

Hui jokingly said that after watching films of Taiwanese New Wave directors Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang, she thought, “Oh Christ, we’re finished!” She was particularly stunned by Edward Yang’s That Day, on the Beach, feeling that they were dealing with another level of reality. Ann Hui continued, “Our films tended to be more melodramatic and entertainment-driven, while their works truly focused on everyday life and human emotions, successfully transforming reality into something meaningful, engaging, and artistic.”

Hui shared that she felt deeply lost at the time while exploring her own filmmaking approach. She invited Wu Nien-jen, screenwriter for Hou Hsiao-hsien, to write a story about her mother, which became the film Song of the Exile. She laughed, recalling, “When I showed this film to a group of Hong Kong students, they said I was imitating the Taiwanese New Wave. I replied, ‘What’s wrong with imitating something good?’” She emphasized that this was actually a very different path to search for something entirely new. “Instead of focusing on handsome men and beautiful women in love stories, I began to pay attention to the elderly, young people, and those who are inexperienced or even lost. However, films like these are very difficult to find investors.”

When asked what qualities are needed to become a director, Hui pointed out that the accessibility of modern technology allows anyone to become one. “With just a mobile phone, you can shoot and edit easily.” She added that a work does not need to be a narrative feature film. As long as it expresses the creator’s ideas, the creator can be considered as a director. She admitted, “At first, I was worried, because when everyone can be a director, the training we once received seemed no longer important. But later, I realized this is actually a good thing.”

“A director should not quit a job in the middle because of difficulties,” Hui stated plainly, emphasizing that being well prepared is essential to getting the job done. She said this perseverance was also why she had stuck with many lousy jobs. She believes directors should try to keep budgets under control and work according to plans. Although such professional virtues may not necessarily be rewarded, she humorously remarked, “Maybe they will only be appreciated in heaven,” drawing laughter from the audience. She added, “Giving yourself certain limits, latitudes and requirements is good.”

Ann Hui’s life has always been inseparable from cinema. The host mentioned Keep Rolling, the documentary directed by Man Lim Chung that chronicles over 40 years of Ann Hui’s filmmaking career. When asked whether there were any films she would remake differently if given the chance. She laughed, saying, “Many.” She continued, “Some people think I’m hypocritical or that I push myself too hard, but that’s not true. I simply have a very high standard of myself.” She also shared sincerely that as long as she is still able to move, she will continue making films. Looking ahead, she expressed her hope to work on television dramas, “The production model for TV dramas today is very different from the past. What I used to make were anthology that each whole series has a different story, whereas I have never shot the TV which is from episode to episode. The television industry is now so mature, and I hope to learn this new dynamics of TV production.”

“When we were still in the halfway of shooting In the Mood for Love, Director Wong Kar-wai suddenly told us that we would start filming its sequel the following week, which later became 2046. There was no script, no clear setup. He only asked me to design and build a massive circus set. I followed a few fragmented ideas and constructed the entire scene, but in the end, everything was cut from the final film. Thinking about it now, it was really a pity.” Man Lim Chung entertained the crowd with anecdotes while recalling his experience working with Wong Kar-wai on 2046 during the forum. This challenging behind-the-scene experience drew hearty laughter and applause from the students.

Another key program of the film gala presentation, the filmmaker forum was held at LPP Convention Hotel as part of the Jogja-NETPAC Asian Film Festival. Renowned Hong Kong Art director Man Lim Chung, director Mandrew Kwan, still photographer Quist Tsang, and emerging short film director Ivan Cheung were invited to participate. Themed “Something You Don’t Know About the Hong Kong Film Industry,” the forum attracted a large number of film students and young cinematheques eager to learn about Hong Kong cinema’s history and future development. The discussion continued actively during the Q&A session, creating a lively atmosphere.

Man Lim Chung emphasized that changes should begin with visual foundations. He explained, “In Hong Kong, production design is not just about aesthetics, it’s about constructing a narrative space. We often have to transform the director’s vision into concrete visuals within extremely tight production schedules.”

“Persistence is the key — how much you truly want to be part of this industry, and how you value it,” said Mandrew Kwan, director of The Remnant who is also a lecturer at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (HKAPA). He shared his perspective on entering the Hong Kong film industry, recalling that he made his first feature film, Coffee or Tea, as a student in 2008, and only completed his second feature more than ten years later, by which time the industry had undergone fundamental changes.

Mandrew Kwan noted that while Hong Kong films once focused primarily on mass entertainment, many contemporary works now engage more closely with social realities. He also mentioned that many graduates of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts have entered the film industry in recent years, including the director and screenwriter of The Narrow Road. “However, filmmaking is not the only path,” he added. “Some graduates choose other creative platforms, such as YouTube, where they can also find their own place. Ultimately, it depends on the creator.”

Discussing how young filmmakers transition into creative careers after graduation, Mandrew Kwan emphasized that creation requires time and life experience. “Many students graduate straight from secondary school and haven’t yet experienced love, heartbreak, or real failure. But these experiences become essential nourishment for creative work.” He continued, “We grew up in Hong Kong with a long tradition of cinema, but we must also face a rapidly changing market. Making good films alone is not enough. We need to find a new voice for our time without abandoning our cultural roots.”

Mandrew Kwan directed his first feature film The Remnant in 2024. He revealed that he is currently preparing for his next project, a horror movie in the script development and funding stage, with plans to begin shooting in the second quarter of next year. The story is inspired by the Cantonese term “juk-yi-yan” (meaning hide-and-seek), which can be traced back to the pirates who used to abduct women for sacrificial purposes along the coast of Hong Kong. The moderator noted a similar Indonesian legend also involving children playing hide-and-seek after 6pm, prompting Mandrew Kwan to remark, “It’s fascinating how different places share stories around the same theme.” The exchange highlighted how cinema can transcend cultures and connect different regions.

“Do you all know Stephen Chow?” one simple question sparked an enthusiastic response from the audience. Still photographer Quist Tsang shared her creative journey, recalling how she grew up watching Hong Kong films. “Whenever I watched Stephen Chow’s films, the unique Hong Kong-style humor always made me laugh out loud.” Seeing even Indonesian audiences are familiar with Stephen Chow’s films, that moment reminded Quist how cinema unites cultures.

As she grew older, Quist became fascinated by gangster films and later developed a strong appreciation for romantic cinema, especially the works of Wong Kar-wai, such as Fallen Angels and In the Mood for Love. She described the slow pacing, Tony Leung’s presence, and even scenes of characters smoking as carrying a distinct cinematic charisma. Deeply inspired by Wong Kar-wai and Johnnie To, particularly Fallen Angels and PTU, Quist said with a smile, “The most magical thing is that I grew up watching Hong Kong films, and now I get to work with the super stars I once admired on screen — it feels like a dream comes true.” She also recalled the excitement and nervousness of photographing Takeshi Kaneshiro for the first time on Sons of the Neon Night.

With over 20 years of experience in photography, Quist transited from magazine and art photography to becoming a film still photographer in 2011. She emphasized that still photography is fundamentally different from behind-the-scenes documentation photography. It requires capturing the “decisive moment” of performance and telling a story through a single image. With the rise of social media, film stills have become a crucial promotional tool, conveying a film’s tone and positioning. Describing herself as “a bit playful,” Quist enjoys shooting action scenes involving explosions, gunfights, and car chases. “Films have taken me all over the world, just like being here today.”

Beyond still photography, Quist is also active in poster design. She spoke about collaborating with directors Alan Mak and Anthony Pun on Extraordinary Misson, where her photography was extended into a full poster series. In 2017, she officially served as poster designer for The Brink, calling it her childhood dream. She later expanded into animation design for Raging Fire, gradually broadening her creative scope.

Quist Tsang also mentioned her participation in the International Film Camp organized by the Asian Film Awards Academy, where she gained deeper understanding in pre-production processes such as screenwriting, funding, and distribution. Reflecting on her evolving roles, she said, “No matter the form, all the work I do is about visual storytelling.”

Emerging short film director Ivan Cheung shared his path into filmmaking. Not originally having a background in film, he majored in statistics at university. His creative journey began when he helped a friend shoot a short film, after which he actively sought opportunities across different production roles, particularly in camera department, to gain hands-on experience.

Ivan Cheung explained that he makes short films to tell his own stories, with the long-term goal of directing feature films. “For young filmmakers in Hong Kong, it often feels like there is an insurmountable mountain ahead, whether in commercial approach or the festival way. It is challenging to create work that is mature enough, making us feel lost.” He said this is why recording and expressing the stories of the younger generation is so important.

Addressing resource limitations, Cheung noted that funding support for short films in Hong Kong is very limited. Although schemes such as Fresh Wave exist, he has spent over ten years writing scripts and applying without success. Nevertheless, he has never stopped creating, with most of his short films being self-funded and produced by a team consisting of only five or six people, aiming to complete projects with minimal cost.

While studying for his postgraduate degree at the Taipei National University of the Arts, Cheung shot his first short film, which centred on a bottle of wine on a beach. “To make the visual more concrete, we actually dug a large hole in the sand to place the bottle,” he recalled. Although the result was not ideal and the process was extremely challenging, he reflected, “When resources are limited, creativity becomes even more important in expressing ideas.”

Regarding the development of the short film market, Cheung believed that Hong Kong’s short film market is relatively small, with limited opportunities to screen in theatres and audiences rarely purchasing tickets solely for shorts. “Most short films are screened at film festivals, and thus many directors aim for international festivals and global audiences.” He also mentioned some non-governmental organizations in Hong Kong, such as film clubs collaborating with cafés, as well as competitions like the ifva Independent Short Film Competition, which provide valuable screening opportunities for students and emerging directors.

The community forum concluded with laughter and warm exchanges, as Man Lim Chung, Mandrew Kwan, Quist Tsang, and Ivan Cheung gathered outside for a group photo with students, bringing the event to a perfect end. JAFF is not merely a place to screen films, but a platform that truly fosters cross-cultural exchanges.

“I never thought that I would make a film that could connect me with so many people around the world.” Robin Lee, director of Four Trails shared his thoughts while attending the Hong Kong Film Gala Presentation in Yogyakarta, organized by the Asian Film Awards Academy, where he spoke with local media about his creative journey and filmmaking experience.

In addition to a series of screenings and talks that fostered cultural exchange, the event placed strong emphasis on industrial connections. Hong Kong filmmakers participated in multiple interviews with local media and actively engaged with industry professionals during “Hong Kong Night” and at the JAFF Film Market.

At the Hong Kong Night reception, Director-General of HKETO Jakarta, Miss Libera Cheng, highlighted the HKSAR Government’s commitment to promoting Hong Kong’s film industry by actively supporting Hong Kong films and filmmakers to take part in international film festivals.

The reception was attended by Hong Kong director Ann Hui, art director Man Lim Chung, still photographer Quist Tsang, emerging directors Mandrew Kwan and Ivan Cheung, alongside Mr. Garin Nugroho, Founder of JAFF; Mr. Ifa Isfansyah, Chairman of JAFF; and Mr. Ajish Dibyo, Executive Director of JAFF, as well as emerging filmmakers from across the region.

Quist Tsang, Mandrew Kwan, and Ivan Cheung also spent time at the JAFF Film Market, engaging in in-depth discussions with local production companies and distributors to explore co-production opportunities. While visiting booths of camera equipment companies, Mandrew Kwan and Ivan Cheung learned that some productions shot in Jakarta may be eligible for tax refunds, and shared insights about funding support available to certain Hong Kong films shot overseas, sparking lively exchanges. The filmmakers remarked on the warmth and enthusiasm of Indonesian audiences and expressed their delight in connecting with them.

Ann Hui candidly shared that what has supported her throughout her career has never been fame or box office success, but a simple and pure motivation — to continue making films, during her media interviews in Yogyakarta.

“I try to overcome any kind of difficulties. As long as I can hold a camera and shoot, I will shoot,” she said. For Ann Hui, financial conditions of filmmaking have rarely dictated her decisions. She has completed multiple projects with almost no budget, often choosing to allocate limited funds to support her crew rather than securing a director’s fee for herself. She added, “If I really like the project enough, even if I do not earn money, if I can get by, I will shoot it.”

Ann Hui reflected on how her creative considerations have shifted over time. While her early films were made primarily for personal expressions, she feels responsible for the audience as well. “I want to make a film which has relevance to what the audience feels, not only for my own satisfaction,” she explained, noting that the greatest challenge today lies in finding subjects that remain meaningful both to her and to people she wants to reach.

Recalling her invaluable experience working in television productions, Ann Hui described that period as a vital foundation of her artistic journey. Many of those works captured footages of traditions and street life that have since vanished, remaining irreplaceable cultural records over the years. “Looking back now, those images are incredibly precious,” she said.

Addressing the current status of Hong Kong cinema, Ann Hui acknowledged that the industry is experiencing one of its lowest cycles, but she insists that such shifts are inevitable. “ Good things and bad things come in cycles.” She spoke frankly that cinema is a luxury in society compared to the necessity of doctors, nurses, and teachers. “You do not need cinema to survive,” she stated with realism.

Although Ann Hui has directed films of varying scales, Ann Hui admitted that larger or Mainland China-funded projects have not always been comfortable. Larger budgets bring higher risks for investors and naturally increase oversight from them, and she respects that responsibility. “They have much more at stake. I have to listen more to what they think the film needs.” However, she noted that too many opinions may compromise the essence of filmmaking. Given a choice, she prefers smaller productions, where trust matters more than supervision.

When asked about actors who stand out to her, Ann Hui expressed deep respect for every actor she has worked with. Speaking of Chow Yun Fat, whom she directed before his rise to stardom, she smiled and said, “He is a nice person and a very good actor.”

Currently, Ann Hui is preparing a television series in collaboration with two other directors. She is honest about her physical limits. “I don’t think I can work nonstop for months anymore.” Yet, she has never considered stopping. Her passion for filmmaking remains undiminished, and she has no regrets in her mindset. “If there is a project I do not get to do, I will do it the next one.”

At festivals like JAFF, Ann Hui said what she values most is the focus on watching films and creative exchange. Red carpets, jewelry, and celebrity culture may be fun, but they are distractions. “The beginning and end is filming itself,” she said, reaffirming her commitment to keeping focus on what truly matters.

Director Robin Lee also spoke extensively with local media about the long creative journey behind his documentary Four Trails, describing it as “my own version of Four Trails.” He revealed that the project took nearly five years to complete and was made entirely without investor support. “This was a passion project between my brother and me, no one asked us to make it,” he said. “That’s why we had to balance our daily jobs while continuing to work on the film.”

Robin Lee said that filming took approximately four to six months, including periods of staying awake for three consecutive days and nights. Due to juggling multiple projects, post-production alone took two years. “My emotions were like a roller coaster,” he admitted. “Sometimes I asked myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ And a few days later I’d think, ‘This is amazing—this is my Four Trails.’”

When asked about the biggest challenge in filming Four Trails, Robin Lee said it was not technical, but emotional balance. While closely following runners through Hong Kong’s four trails, the crew had to build trust while maintaining distance. “They knew who we were, so the camera didn’t interfere, but we still had to control ourselves and keep emotional boundaries.”

He also shared the unpredictability of documentary filmmaking. “I might film someone at the 20-kilometre mark and not see them again until 120 kilometres later. I have no idea what happened to them in between.” The most emotionally overwhelming moment, he said, was when runners crossed the finish line. “At that moment, all the emotions pour out. Even now, thinking about it still gives me goosebumps.”

Robin Lee emphasized that the power of this film lies not in how tough the route is, but in the story of ordinary people attempting an extraordinary challenge. “They’re not professional athletes. They’re just ordinary people, like you and me.” Through Four Trails, he hopes to show a obscure side of Hong Kong. “For me, it’s a way of showing my home from a different perspective.”

Robin Lee also shared that he never expected his film to resonate with audiences around the world, which came as a pleasant surprise. He described himself as still relatively new to Hong Kong’s film industry. Before doing Four Trails, he was making short documentaries and commercial projects. “This film was sort of just really wanted to make a film, and I wanted to take the experience I had from filming adventure films around the world to Hong Kong,” he noted that sports adventure films rarely existed in Hong Kong before Four Trails, and that the documentary fills the gap.

Speaking about how Hong Kong’s diverse landscape help the local film industry, Robin Lee emphasized that Four Trails relies heavily on the city’s landscape. “ When you show someone a photo of Hong Kong, the photo they see is the dense cityscape that’s like the image everyone has. But I was born and raised in Hong Kong, and I love being in the mountains. The image that I see of Hong Kong is from the mountains looking down.” He hopes audiences will see the striking contrast between the city and the mountains existing right by each other. “I love filming in Hong Kong, and I love filming the mountains, so this is a great opportunity to combine both.”

On balancing personal stories, the race itself, and Hong Kong’s landscapes in Four Trails, Robin Lee stated that human stories are the backbone of the film. “The landscape is just secondary. What matters most is all about telling their stories.” During filming, he constantly considered when and where he could interact most meaningfully with the runners, and how to showcase Hong Kong’s natural beauty.

He described the balance as something that emerged organically rather than being deliberately planned. “At the end of the day, it just came down to what I felt right. It was like this is just what feels good to me, and this is the direction I want to go in,” he added.

“In Hong Kong, we rarely get to spend quality time with seniors like Man Lim Chung. But here, running together and visiting the world heritage site Borobudur, we built a friendship that transcends generations,” director Mandrew Kwan shared his feelings at the Hong Kong Film Gala Presentation in Yogyakarta. The trip has fostered unique bonds among the delegates.

The event returned for its second edition to enthusiastic acclaim. Under the theme “Together We Dare to Direct,” the programme showcased a curated selection of Hong Kong films. A special highlight was the “Director Ann Selection,” featuring July Rhapsody , A Simple Life , and the documentary Keep Rolling directed by Man Lim Chung, offering a retrospective of the legendary filmmaker’s career. Together with screenings of Sons of the Neon Night, Four Trails, The Remnant, Another World , Someone Like Me , the restored classic The Killer , and the “Hong Kong Short Film Collection,” the Gala presented a comprehensive view of the heritage and innovation of Hong Kong cinema. A delegation including Ann Hui, acclaimed Hong Kong Film Awards-winning art director Man Lim Chung, directors Robin Lee, Mandrew Kwan, and Ivan Cheung, and still photographer Quist Tsang travelled to Yogyakarta to engage deeply with local audiences and promote Hong Kong cinema to Indonesian cinephiles.

In the post-screening Q&A for the restored classic July Rhapsody , Ann Hui and Man Lim Chung reunited on stage to revisit their first collaboration. Man revealed that it was his first time working with Ann Hui, who was already highly acclaimed, while he was still early in his career, making him nervous at that time. Recalling the casting process, both filmmakers spoke highly Karena Lam, who was a newcomer back then, for her “unparalleled aura” which was perfect for the role.

Speaking about working with superstars Jacky Cheung and Anita Mui, Man shared a little-known anecdote, “Audiences often wonder if stars refuse to wear ordinary or old clothes. On the contrary, they were incredibly cooperative. To capture the film’s weary atmosphere, they willingly wore the second-hand, worn-out clothes we bought without complaint, solely focused on presenting the best state for their characters.”

During the Q&A for Keep Rolling, Man Lim Chung explained why he decided to make the documentary. While Ann Hui is widely recognised as an award-winning master filmmaker, including Lifetime Achievement Awards. Man, who had worked closely with her for many years since July Rhapsody, described that Ann’s everyday side was rarely seen. He wanted to capture that side of her life. He described Ann as someone who lives simply, enjoying everyday pleasures, such as egg tarts and milk tea at local cafés (cha-chaan-teng).

Man also shared that Ann Hui is not particularly fond of being filmed. Keep Rolling premiered as the opening film of the Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF). Although Ann attended the premiere and posed for photos, she felt shy about seeing her face on the big screen and chose not to watch the film. It was only three or four months later when the film was officially released, after hearing positive feedback from friends, that she finally decided to see it.

As an art and costume designer, Man candidly admitted that he does not consider himself a professional director. On Keep Rolling, he also handled cinematography and editing, and humbly noted that some camera movements were not particularly polished. “I’m not a famous director,” he said with a smile, hoping audiences would still enjoy the film.

Man also recalled a humorous incident during filming. Nervous about not having enough footages, he spent nearly three years filming Ann Hui almost nonstop whenever he saw her. Once, while they were having a meal together and chatting casually about other people, Ann suddenly realised she was being filmed and became angry, saying, “Stop making this film, don’t release it!” Thankfully, she soon calmed down. After that, they agreed not to film her endlessly. Instead, they conducted a final in-depth interview to ask everything Man wanted, followed by one last day of filming Ann’s daily life, which eventually completed the filming of the documentary.

Still photographer Quist Tsang shared her visual design concepts during the Sons of the Neon Night Q&A. She explained that since the film is black and white, she focused on retaining that base while adding splashes of bright red, like blood, for visual impact, striking visual impact and the aestheticization of violence.

Compared to other productions she had worked on, Quist described the atmosphere on set of Sons of the Neon Night as particularly tense. Crew members rarely spoke, quietly waiting for the director’s instructions.

Some Indonesian audience members noted that the role of a “still photographer” does not exist in their local industry and were curious about what the job. Quist explained that still photography requires a more detached perspective. She studies upcoming scenes with the crew in advance to anticipate critical moments and capture split-second images. She also noted that stills play an important role in film promotion. Images and videos are often more immediately engaging and attractive than text, helping audiences decide whether to watch the film or not.

“If you don’t have any scars from shooting gunfight films, how can you actually say you’ve filmed a gunfight film?” she joked, describing her experience photographing action scenes. While gunfights and explosions are dangerous, she said her priority is always to find the best position to capture the decisive moment. She expressed pride in contributing to such an action-driven film as a still photographer.

“Wow! I had no idea Hong Kong had scenery like this!” many audiences exclaimed during the post-screening discussion of the documentary Four Trails. Director Robin Lee showcased Hong Kong’s little-known yet breathtaking mountain landscapes, sparking lively discussion. Audiences were also amazed by the idea of running through mountains for three days without sleep.

Many were curious about how Robin and his team managed to capture such moving moments without running the entire race with the runners. As a filmmaker who frequently shoots trail-running documentaries, Robin was already familiar with Hong Kong’s four trails and conducted extensive research beforehand, learning about each runner’s background, plans, and estimated arrival times at different checkpoints, so the crew could be ready in advance. However, unexpected situations still arose. “I might plan to film someone running uphill at point A, but for some reasons they end up arriving at point B instead, and we miss the shot,” he said. That is why his team tried to capture as much footages as possible. Robin believes the unique enchantment of both documentary filmmaking and the endurance sports lies in this uncertainty. For example, the fastest runner in the film only confirmed his participation three months before the race, with limited preparation. These unpredictable, passionate stories, he said, are what make the documentary truly precious.

During the post-screening Q&A for The Remnant, director Mandrew Kwan shared his love for the romantic brotherhood often found in John Woo’s films, and his desire to recreate that spirit in his own work. He reflected on how films from that era portrayed romance, not just between people, but within the city itself, which deeply inspired him.

When asked about the production timeline, Mandrew revealed that the entire shooting lasted just over ten days, surprising many audience, “so this is how fast Hong Kong filmmakers work!” they remarked. Mandrew added that as this was his first feature film and the schedule was extremely tight, there were many things did not turn out as what he had originally planned, and he felt he could have done better.

Director Ivan Cheung said he was delighted to bring his short films to Indonesia and was pleasantly surprised that the screenings were almost full house. “I didn’t expect the audience here to be so supportive of short films,” he said. Many local Indonesian short filmmakers attended the post-screening session, leading to enthusiastic exchanges.

When the audience knew that Ivan worked with a very small budget, they were impressed by the creativity of his films. They praised the strong visual approach of the black-and-white Tomatoes are Poisonous and the intentionally unstable camera movement in The Apple of My Eyes, noting that the sense of chaos was handled effectively.

After the screening, a local short film director even took an egg out and gave it to Ivan as a greeting gift, jokingly said that it was a random item found in his bag. Ivan cheerfully accepted the unusual but memorable gift.

Under the theme “Together We Dare to Direct,” this year’s Hong Kong Film Gala Presentation – Yogyakarta traced a journey from classic reflections by Ann Hui and Man Lim Chung to the creative experiments and market explorations of emerging filmmakers. Through a series of lively post-screening discussions, the event highlighted the passing of creative spirit across generations and the courage to innovate, bringing the programme to a close with warm applause and opening a new chapter in cultural exchange between Hong Kong and Indonesia.

Anchored by the theme “Together We Dare to Direct,” the Yogyakarta edition demonstrated the spirit of Hong Kong filmmakers, from Ann Hui’s enduring passion and her classic retrospectives with Man Lim Chung to the new generation’s bold exploration of new markets. The event concluded amidst warm applause, marking another successful chapter in the cinematic dialogue between Hong Kong and Indonesia.

Asian Film Awards Academy

The Asian Film Awards Academy, a non-profit organization, was founded by Busan, Hong Kong and Tokyo International Film Festivals with the shared goal of celebrating excellence in Asian cinema. Aiming to promote and recognise Asian films and its talents, AFAA highlights, strengthens and develops Asian film industry through the annual Asian Film Awards and several year-round initiatives.

Our year-round events and programmes are held with the objectives to promote Asian films to a wider audience, expand the film market within Asia, and build and sustain connections among Hong Kong and international film professional. Masterclass Series – in conversation with filmmakers, Journey to the fest – Student Visit to International Film Festivals, Asian Cinerama – Film Roadshow, and Young Film Professionals Programme – overseas training and work-placement, are examples of our year-round programmes. These programmes could not have held successfully without the financial support of Cultural and Creative Industries Development Agency (CCIDA), formerly known as Create Hong Kong, and Film Development Fund (FDF) of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government. AFAA has worked to promote, educate, inform and develop knowledge, skills and interest in Asian cinema among the industry, students and audiences in Asia and beyond with the support of film festivals and cultural organizations.

Cultural and Creative Industries Development Agency

CCIDA, formerly known as Create Hong Kong is established in June 2024and is a dedicated office set up by the HKSAR Government under the Culture, Sports and Tourism Bureau. It provides one-stop services and support to the cultural and creative industries with a mission to foster a conductive environment in Hong Kong to facilitate the development of arts, cultural and creative sectors as industries.

Film Development Fund

The FDF was first set up by the Government in 1999 to support projects conducive to the long-term development of the film industry in Hong Kong. Since 2005, the HKSAR Government has injected a total of $1.54 billion into FDF to support Hong Kong’s film industry along four strategic directions, namely nurturing talent, enhancing local production, expanding markets and building audience. In the past, FDF has supported a number of film productions and other film-related projects through various film production funding schemes and other film-related project schemes.

Please contact us if any questions,

Email: info@afa-academy.com

Tel: +852 3195 0608

Website: www.afa-academy.com